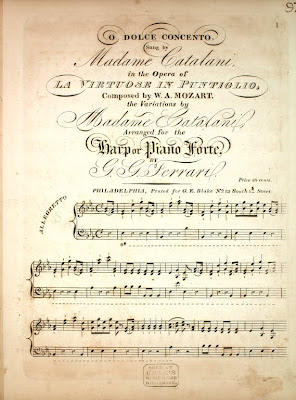

I fear I have done Monsieur Gautrot a disservice by hoisting that question mark over his claim to have composed for the Theatre Royal in Campbell Street, Hobart Town, in May 1839, variations upon Mozart’s “O Dolce Concento.” That charming, brief ensemble piece was already famous, and the practice of transposing it for soprano and composing and performing variations upon it was by then well established. Today we know the piece not by the Italian titles of “O dolce concento,” “O dolce armonia,” or “O cara armonia,” which last iteration was chosen for the vocal score published in London in about 1813, but as “Das klinget so herrlich, das klinget so schön,” which is sung by Monostatos and a chorus of ridiculous slaves in Act I, sc. iii of Mozart’s last opera The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte) (K. 620) (1791). On the other hand, there can be no better demonstration of the chaotic manner in which music and lyrics were randomly harvested for late Regency concert programs than this charming adaptation and set of variations (above) that is presumably rather similar to the kind of thing the Gautrots concocted for Sydney and Hobart in 1839: “O Dolce Concento, Sung by Madame Catalani, in the Opera of La [sic] Virtuose in Puntiglio, Composed by W. A. Mozart [sic], the variations by Madame Catalani, Arranged for the Harp or Pianoforte, by G. G. Ferrari. Philadelphia, printed for G. E. Blake.” In this instance, either Angelica Catalani (1780–1849) or Giacomo Gotifredo Ferrari (1759–1842) were very muddled indeed, or laboring under a misapprehension, because the text of “Le Virtuose in Puntiglio: Or, The Punctilious Singers, A Comic Opera, in Two Acts, as represented at The King’s Theatre, in the Hay-Market, with additions, by S[erafino]. Buonaiuti,” was published in London in 1808, and made it absolutely clear that the composer was not Mozart at all, but Valentino Fioravanti (1799–1877). The aria devised for Madame Catalani survives in dozens of editions, published not just in Philadelphia, as in this case, but also in Paris, Edinburgh, London, Boston, Vienna, and Amsterdam, and as late as 1871 a fresh orchestration was arranged by Friedrich Kücken (1810–1882) and published in Leipzig by Bartholf Senff (1815–1900). The original variations may have been composed by Ferdinando Paër (1771–1839), because the earliest edition (Paris: Naderman, 1817) attributes to him the “variations chantées par Madame Catalani au Théâtre royal italien.” In fact in the fifty years following the first performance of The Magic Flute, dozens of other sets of variations on “Das klinget so herrlich, das klinget so schön” were composed, arranged, and performed. One translation into English began unpromisingly: “Away with melancholy, Nor doleful changes ring.” There were instrumental versions for bugle, bassoon, flute, harp, piano duet, harp and piano, solo piano, banjo, guitar, and harmonium. In London Felice Radicati (1775–1820) turned the melody into a “canone a tre voci” with chorus, orchestra, and harp. The flautist Louis Drouet (1792–1873) toured with his Variations brillantes et favorites...sur l’air de Mozart O dolce concento exécutées dans plusiers concerts à St. Petersbourg, Vienne, Munich, Milan, Berlin, Florence (Milan: Ricordi, ca. 1825), and an excitingly different “Variations brillantes sur O dolce concento” by Henri Herz (1803–1888) was in 1834 printed in Paris. There is a still different version by Charles Czerny (1791–1857), and an early arrangement for voice and guitar appears in the Entire New and Complete Instructions for the Guitar by a Professor (London: George Astor, ca. 1799). The theme also turns up as a temperance hymn by John Pierpont (1785–1866); as a fraternity glee for Bowdoin College (1839); as a tune for Scottish fiddle, as well as a “Masonick” song, which, of course, doubles back to the plot of The Magic Flute. This is the context in which Monsieur Gautrot made his own offering to the public of Hobart Town in May 1839. He must have been sure that his Tasmanian audience would recognize the real thing when Madame Gautrot sang it, and also appreciate the Janus-like, platypodic deftness of his own variations upon the original. (Besides being a violinist of note, M. Gautrot had an apparently charming light tenor voice.) However, neither he nor Madame can have anticipated the outrageousness with which that party of ladies and the indolent gentleman expropriated Sir John Franklin’s vice-regal box, the queer and opposite incident that caused such consternation and, thankfully, demonstrations of loyalty before Colonel Elliott’s band of the 51st struck up their ouverture militaire. Who were these defiant young people, and what presumably political axe did they seek to grind so publicly?

No comments:

Post a Comment